At my previous employer, our goal was to stain tissue samples such that a pathologist could examine them microscopically and easily make unambiguous diagnoses of disease state. Experiments typically involved getting subjective judgments from pathologists about which samples were “better” in some way. How do you do statistics on those type of results?

When comparing the results from a control condition with the results from a single experimental condition, the results would often come back as “good” vs. “bad”, “better” vs. “worse”, “unacceptable” vs. “acceptable” vs. “exceptional” or a similar ranking. In some parts of the business, it was customary to provide the rankings in a pseudo-numeric form – this stain has an intensity of 3.5 while this other stain is a 4.0. But even though the scores look like they are on an interval scale, they are actually ordinal. For the same scorer, the difference between a 3.5 and 4.0 may not be the same as the difference between a 2.5 and a 3. And different scorers can give different results.

Before coming to work for this employer, I had always done experimentation where the results were on an interval scale. I was initially at a loss as to how to deal with the ordinal results I had to work with. After exploring my options, one analysis method I have come to enjoy is the Wilcoxon Matched Pairs analysis (also known as the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test (Broken Link), not to be confused with the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test or Mann-Whitney U Test. I tend to say “matched pairs” to keep myself and others from getting confused.) The test estimates how likely it is that two sets of correlated samples have the same median.

The experimental set up is easy, matched pairs of control and experimental samples. It’s a non-parametric test that makes few assumptions about the underlying distribution from which the data is drawn. It’s easy to explain to scientists without much statistical background.

So, I created a tool to help myself and my colleagues analyze such data. It’s written in Java and available on a public repository on HelixTeamHub.

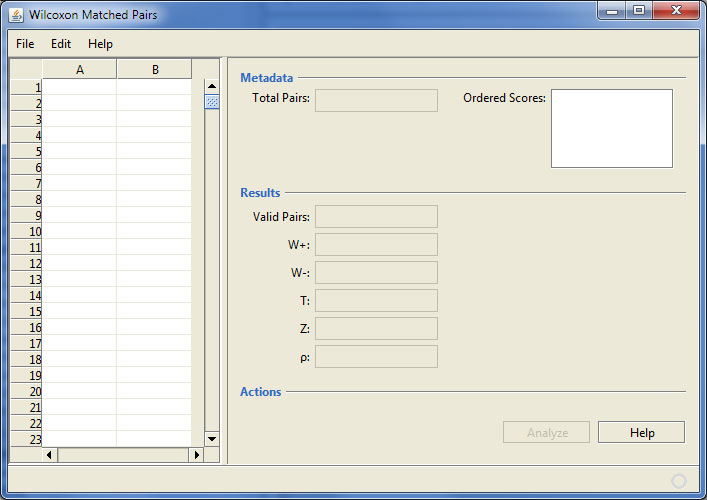

Here’s a screen shot of the application after it starts up:

Wilcoxon Matched Pairs program startup

Wilcoxon Matched Pairs program startup

The interface displays an area for data input. Although data can be entered here, it is really intended that data be loaded from a specially formatted data file, as explained in the “readme.md” file in the repository. (This is an example of my dissatisfaction with data entry components available for Java as elaborated here.)

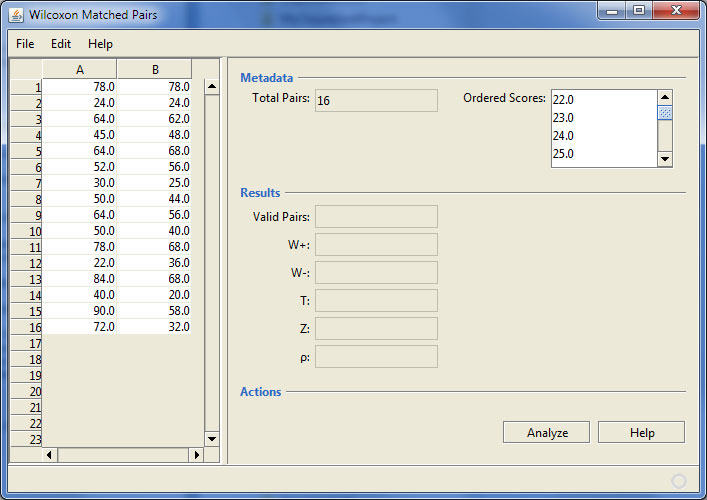

Once a suitable data file is loaded, the data and some metadata are available for inspection.

The Wilcoxon Matched Pairs program after loading some data

The Wilcoxon Matched Pairs program after loading some data

In this example the data appears to be on an interval scale, but in fact, it is ordinal. The program also shows the number of data pairs (useful for larger datasets) and there is a drop down that shows all of the valid scores in order.

A click on the “Analyze” button does the work.

The Wilcoxon Matched Pairs program after analyzing some data

The Wilcoxon Matched Pairs program after analyzing some data

The analysis shows the number of usable (non-tie) data pairs as well as some intermediate values in the calculations. The value of p is used to judge the significance of the difference in medians. In this case, the value of 0.035 is usually considered to be significant.

This program operates a little differently than similar ones in that most programs calculate the exact p value for small numbers of observations, but use a normal approximation for larger numbers of observations. This program uses the exact calculation for all numbers of observations. In my own work, even when there are thousands of pairs of data, the exact calculation occurs almost instantly, so why add the additional complication.

The code in the repository is a NetBeans project. This project was created with an old version of NetBeans, but has been run and tested with NetBeans 7.0.1. However, the program was created with the Swing Application Framework (Broken Link) and NetBeans 7.0.1 is the last version to support the abandoned framework. The project won’t compile with NetBeans 7.1 or later. What a pain. Perhaps future work will continue by adapting the project to the Better Swing Application Framework (Broken Link). Or maybe it’s finally time to start learning the NetBeans Platform for ongoing desktop development work.